#30. Sandhill Crane

These birds are naturally gray and their heads are topped with a crimson crown. Most sandhill cranes live in freshwater wetlands. They are opportunistic eaters that enjoy plants, grains, mice, snakes, insects, or worms. They often dig in the soil for tubers and can sometimes cause significant crop damage, which brings them into conflict with farmers. During mating, pairs vocalize in a behavior known as “unison calling“. They throw their heads back and unleash a passionate duet—an extended litany of a coordinated song.

Sandhill cranes have one of the longest fossil histories of any extant bird. A 10-million-year-old crane fossil (Miocene Epoch) from Nebraska was found and is said to be of this species, but this may be from a prehistoric relative or the direct ancestor of sandhill cranes. The fossil was found to be structurally the same as the modern sandhill crane. Even though there is evidence that proves that they existed 10 million years ago, their average life span in the wild is about 20 years.

#29. Lice

Lice are tiny, wingless, parasitic insects that feed on your blood. They are obligate parasites, living externally on warm-blooded hosts which include every species of bird and mammal, except for monotremes, pangolins, and bats. Lice are easily spread — especially by schoolchildren — through close personal contact and by sharing belongings, like hair combs, since lice only move from host to host by using their front claws to grasp onto a nearby hair shaft.

According to the entomologist Vincent Smith, lice are old, proliferated during the Late Cretaceous, and must have been living on something. However, what those “somethings” were, remains unclear, since there were already plenty of small mammals and feathered dinosaurs running around. The lice fossils found in those furs and feathers weren’t exactly as the lice are today. The first appearance of lice fossils as the species we know nowadays dates back to 20 million years ago.

#28. Echidna

Echidnas, sometimes known as ‘spiny anteaters’ belong to the family of the monotremes and are one of the last surviving species of mammals that lay eggs. They were named after Echidna, a Greek mythological figure known as the ‘mother of monsters’. Echidnas do not tolerate extreme temperatures; they use caves and rock crevices to shelter from harsh weather conditions.

Molecular clock data suggest echidnas evolved between 20 and 50 million years ago, descending from a platypus-like monotreme. This ancestor was aquatic, but echidnas adapted to life on land. Echidnas are very timid animals. When they feel endangered they attempt to bury themselves, or if exposed, they will curl into a ball similar to that of a hedgehog using their spines to shield them.

#27. Purple Frog

Also known as “pig-nosed frog“, these frogs are restricted to the Western Ghats of India. They spend the majority of their lives underground and only come to the surface for two weeks every year, at the start of the monsoons, for mating purposes. They don’t even need going out for food since they are able to live on a diet of the food that exists underground, which is mainly termites. Maybe that’s how they made it this far!

Unfortunately, the purple frog is listed as ‘endangered’ by the IUCN Red List and is threatened by deforestation from expanding cultivation (due to coffee, cardamom, and ginger plantations), in addition to consumption and harvesting by local communities. It is a pity that an animal that inhabited the Earth for at least 50 million years prior to any other frogs in India is on the brink of extinction due to human activity.

#26. Crocodile

Crocodiles or true crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. Crocodiles are the most vocal of all reptiles, producing a wide variety of sounds depending on species, age, size, and sex. Depending on the context, some species can communicate over 20 different messages through vocalizations alone. Some of these vocalizations are made during social communication, especially during territorial displays towards the same sex and courtship with the opposite sex.

Crocodiles possess some advanced cognitive abilities: they can observe and use patterns of prey behavior, such as when prey comes to the river to drink at the same time each day. Crocodiles place sticks on their snouts and partly submerge themselves. When the birds swooped in to get the sticks, the crocodiles then catch the birds. It is not surprising that they already inhabited the Earth 55 million years ago.

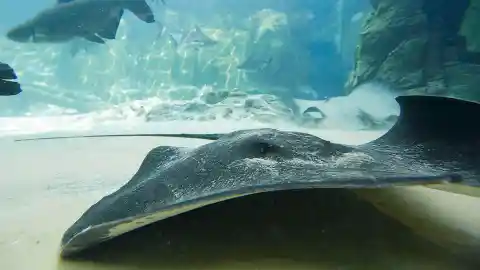

#25. Giant Freshwater Stingray

These ancient fish can reach 16.5 feet (5 meters) long and weigh up to 1,320 pounds (600 kilograms). At half the length of a bus, the gargantuan freshwater stingray may be the largest fish swimming in freshwater on Earth today. Large stingrays have been known to pull boats upstream and even underwater.

Despite its mega dimensions and toxicity, these nomadic species remain elusive and cloaked in mystery, only first being identified by scientists less than 20 years ago. Populations of giant stingray are faring better than other giant fish. Experts suggest this may be because of the depth of the river these species inhabit, as well as the fact that they are so difficult to catch. They are good hiders because they are believed to be at least 60 million years old.

#24. Cow Shark

These sharks have long and fairly slender bodies. Some species can grow to over 5m in length. Cow sharks are ovoviviparous, with the mother retaining the egg cases in her body until they hatch. They feed on relatively large fish of all kinds, including other sharks, as well as on crustaceans and carrion. Not much is known about these sharks as they tend to spend most of their time in very deep water.

Members of the Cow Shark family are considered to be the most primitive of all living sharks because they have a skeleton similar to that seen in the fossils found of extinct sharks (of around 60 million years). They also have a relatively primitive digestive system compared to other sharks, and the fact that they have either six or seven pairs of gill slits, instead of the usual five, also links them to the sharks of the past.

#23. Frilled Shark

Frilled sharks may capture prey by bending their bodies and lunging forward like a snake, that’s is why they are also known as ‘sea serpents’. The frilled shark’s mouth is lined with 25 rows of backward-facing, trident-shaped teeth—300 in all. And as if its teeth weren’t freaky enough, the frilled shark has spines, called dermal denticles, lining its mouth. Enough to assure you bad dreams at night.

Several early authors believed the frilled shark to be connected with the cladodonts, a now-obsolete taxonomic grouping containing forms that thrived during the Palaeozoic era. Some others suggested it was instead related to the hybodonts, which were the dominant sharks during the Mesozoic era. It is not clear were this shark comes from, but it is supposed to be threatening the ocean’s depths for at least 95 million years.

#22. Bee

Bees play an important role in pollinating flowering plants and are the major type of pollinator in many ecosystems that contain flowering plants. It is estimated that one-third of the human food supply depends on pollination by insects, birds, and bats, most of which is accomplished by bees, whether wild or domesticated.

A bee fossil from the early Cretaceous (~100 mya), the Melittosphex Burmensis, is the oldest known species of bee. The species was discovered as an amber inclusion in the year 2006 by George Poinar, Jr., a zoologist at Oregon State University. The amber was found in a mine in the Hukawng Valley of northern Myanmar. The species is considered an extinct lineage of pollen-collecting Apoidea sister to the modern bees.

#21. Green Sea Turtle

The species’ common name does not derive from any particular green external coloration of the turtle. Its name comes from the greenish color of the turtles’ fat, which is only found in a layer between their inner organs and their shell. As a species found worldwide, the green turtle has many local names. In the Hawaiian language, it is called ‘honu’ and it is locally known as a symbol of good luck and longevity.

The world’s oldest sea turtle fossil shows the ancient animal swam the oceans at least 110 million years ago when dinosaurs still roamed the Earth. The now-extinct Desmatochelys Padillai turtle skeleton was found in Villa de Leyva, Colombia. The cool thing about this turtle is that it’s really old, but it’s not very primitive… Maybe there exist older species yet to be found. To see more specimens of the Testudine family who are also long-time survivors, check slide #15.

#20. Duck-billed Platypus

The platypus is among nature’s most unlikely animals, they were believed to be the victims of a hoax, described as a hodgepodge of a duck (bill and webbed feet), a beaver (tail), and an otter (body and fur). It is one of the few species of venomous mammals: the male platypus has a spur on the hindfoot that delivers a venom capable of causing severe pain to humans. The venom system is used by males on one another as a weapon when competing for females, taking part in sexual selection.

Molecular clock and fossil dating suggest platypuses split from echidnas around 19–48 million years ago. The oldest discovered fossil of the modern platypus dates back to the Quaternary period. The fossil is thought to be about 110 million years old. Unlike the modern platypus (and echidnas), Teinolophos lacked a beak.

#19. Martialis Heureka

The generic name means “from Mars” and was given due to its unusual morphology. These ants are pale in color, and they lack eyes which suggest that they lead a subterranean life in covered low-light environments, like leaf litter or rotting wood, possibly foraging on the surface during the night to pray on small litter organisms.

Fossils of this species were found in the Amazon rainforest near Manaus, Brazil. It belongs to the oldest known distinct lineage to have diverged from the ancestors of all other ants. These fossils are believed to be 120 million years old.

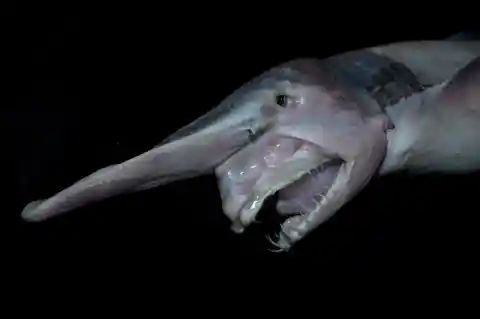

#18. Goblin Shark

Among all sharks, this species stands out for its unusual appearance characterized by a flattened snout that protrudes from the top of its head and by a mouthful of teeth that resemble nails. It detects prey by combining its senses of smell and electro-perception. If it is near the ocean floor and discovers a victim, it observes it from below without moving. It is not a skilled or fast swimmer, so it moves slowly towards its food to avoid being discovered. However, he is, in fact, an efficient ambush predator. They date back to the prehistoric era, about 125 million years ago.

As these creatures are deep-sea residents, with few coming into shallower waters, Goblin Sharks are not considered a threat to humans. However, the opposite is true. Their few known threats are the accidental catch, mainly on the coasts of Japan. Besides, their strange jaws arouse curiosity to collectors who can pay from 1,500 to 4,000 dollars to get one. For the moment, as it is rarely seen and captured, the goblin shark status in the Red List of the UICN is “Minor Concern”.

#17. Sturgeon

Sturgeon range from subtropical to subarctic waters. They can be found in greatest abundance both in the rivers of southern Russia and Ukraine and in the fresh waters of North America. Their toothless mouth, on the underside of the snout, is preceded by four sensitive tactile barbels that the fish drags over the bottom in search of invertebrates, small fishes, and other food.

Sturgeons date back to the prehistoric era finding them in the Triassic, some 200 million years ago. They have been referred to as “primitive fishes” because their morphological characteristics have remained relatively unchanged since the earliest fossil record. Unfortunately, several species of sturgeon are harvested for their roe which is processed into the luxury food caviar. Overexploitation has brought most of the species to critically endangered status, at the edge of extinction.

#16. Tuatara

Tuataras are reptiles endemic to New Zealand. Their name derives from the Māori language, and means “peaks on the back”. Tuataras are unusual because they are nocturnal and like cool weather (they do not survive well over 25 degrees centigrade but can live below 5 degrees, by sheltering in burrows). However, their most curious body part is a photoreceptive eye, “the third eye” on the top of the head which is sensitive to light and may help the tuatara judge the time of day or season.

A tuatara’s average life span is about 60 years but they probably live up to 100 years. The single species of tuatara is the only surviving member of its order, which flourished around 200 million years ago, all species except the tuatara declined and eventually became extinct about 60 million years ago. Rats are considered the most serious threat to the survival of tuatara because they are easily transported as stowaways on boats and famous for being nest robbers.

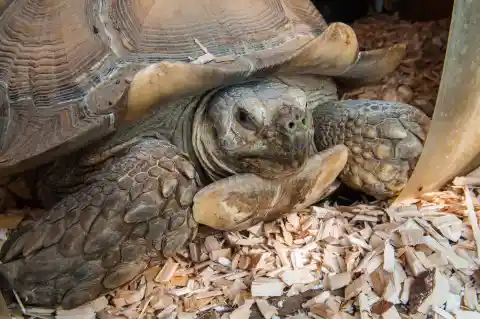

#15. Tortoise

Tortoises, like their cousins, the Turtles, have a hard shell, ‘the caparace’ which protects their body and which is covered with scutes made of keratin (the same protein that our fingernails are made of). The carapace can help indicate the age of the tortoise by the number of concentric rings, much like the cross-section of a tree. They are particularly distinguished from turtles by being land-dwelling, while many (though not all) turtle species are at least partly aquatic.

Tortoises generally have life spans comparable with those of human beings, however, some tortoises have been known to have lived longer than 150 years. Paleontologists in south-western Germany have discovered the oldest ever tortoise fossil in the world (clocking in at a whopping 200 million years) which has been dubbed ‘the granddad tortoise’. The creature’s anatomy has enabled scientists to establish a closer relationship between tortoises and lizards, crocodiles, and birds, discrediting previous theories that they originated from the very first dinosaurs.

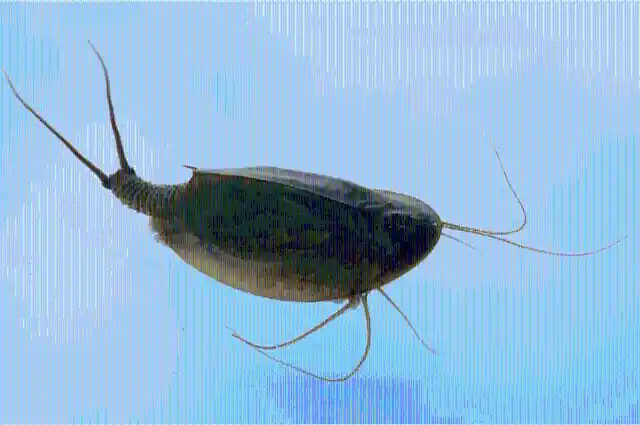

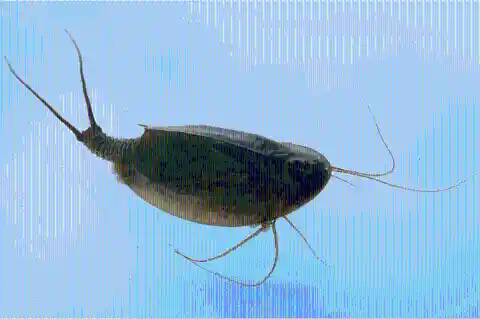

#14. Tadpole Shrimp

Tadpole shrimps (or “triops“, due to the 3 eyes they have) typically dwell at the bottom of bodies of water, feeding on organic debris or preying on small aquatic animals and larvae. Their eggs, which are highly resistant to desiccation, may survive in the soil for many years -up to two decades- after temporary pools have dried up, and hatch when the pools have refilled with water. Tadpole shrimps develop rapidly, reaching maturity in as little as 8 days. A female Triops starts reproducing 10 days after hatching and leaves hundreds of eggs in their lifetime. Triops usually live for 6-12 weeks.

The British species of Tadpole shrimp is actually the oldest in the world, and it is at least 220 million years old. This means it was swimming around in pools when the dinosaurs were roaming our planet. Tadpoles shrimps live in seasonal brackish (slightly salty) or freshwater pools, which dry out in the summer. Utilizing such an inhospitable and difficult habitat is believed to be one of the reasons why this group of animals has been able to survive for so many millions of years.

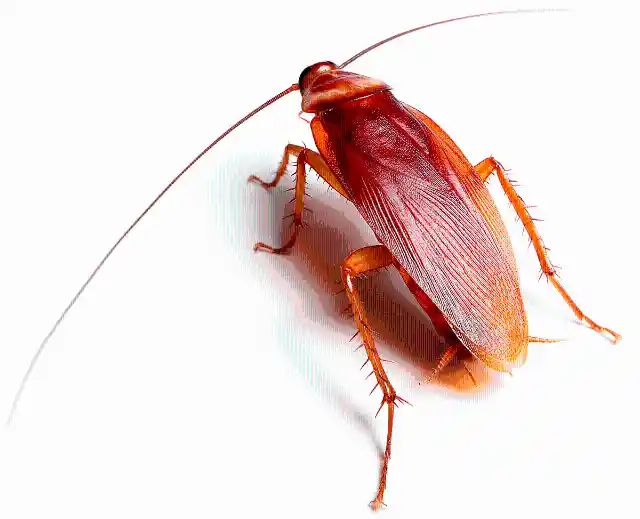

#13. Cockroach

Cockroaches are very resilient pests: they can spend 75% of their time resting and can withstand temperatures as cold as 32 degrees Fahrenheit. A cockroach can live for a week without its head. Due to their open circulatory system, and the fact that they breathe through little holes in each of their body segments, they are not dependent on the mouth or head to breathe. They even can survive a month without food. The roach only dies because, without a mouth, it can’t drink water and dies of thirst. A cockroach can hold its breath for 40 minutes, and can even survive being submerged underwater for half an hour.

Cockroaches can run up to three miles in an hour, which means they can spread germs and bacteria throughout a home very quickly. A female German cockroach (the most common species) lays about 20 to 40 eggs, with an average incubation rate of 28 days, and will produce an estimated four or five oothecae -the capsule carrying the eggs- in her lifespan. That’s about 200 offspring. These facts prove that cockroaches are some of the most adaptable creatures on Earth, and it is not surprising that they have inhabited our planet for 250 million years, since the Carboniferous era.

#12. Horseshoe Shrimp

Horseshoe shrimp refers to any member of the marine crustacean subclass Cephalocarida, named because of the curving, horseshoe-like shape of the body. Cephalocaridans are found from the intertidal zone down to a depth of 1,500 m (4,900 ft), in all kinds of sediments. Cephalocaridans feed on marine detritus. To bring in food particles, they generate currents with the thoracic appendages like the branchiopods and the malacostracans. Food particles are then passed anteriorly along a ventral groove, leading to the mouthparts.

This little crustacean wasn’t just around when dinosaurs roamed the earth, it was around when they were evolving. Though no fossil record of cephalocaridans has been found, most specialists believe them to be primitive among crustaceans, they are believed to be 250 million years old.

#11. Lamprey

Lampreys are an ancient extant lineage of jawless fish. Their mouth is a permanently open ring, filled with a vicious-looking set of teeth. However terrifying these teeth may be, it is actually tiny sharp structures on the lamprey’s tongue that scrape away fish scales. One lamprey kills about 40 pounds of fish every year. Lampreys have a remarkable ability to heal themselves even after severe nerve damage.

Like some other primitive fish, lampreys don’t have bones: their skeleton is cartilaginous. Lamprey fossils are rare because cartilage does not fossilize as readily as a bone. The first fossil lampreys were originally found in Early Carboniferous limestones, 360 million years ago. None of the fossil lampreys found to date have been longer than 10 cm (3,9 inches), and all the Paleozoic forms have been found in marine deposits.

#10. Elephant Shark.

The elephant shark or “ghost shark” is easily identified because of their very large, high-set eyes, and the club-like structure at the end of their snouts. Their protruding snout is made to search for food prey in the sand and is highly sensitive to electric fields and movement. They have a dangerous spine just ahead of their dorsal fin, and sport fishers should handle this shark with caution.

The elephant shark has the slowest-evolving genome of any vertebrate. It is not actually a true shark but belongs to a group known as ratfish, which diverged from sharks about 400 million years ago. They have skeletons made of cartilage, a trait that is now rare among vertebrates but was the norm when they first evolved. On the other hand, critics say this view of ratfish as evolving slowly fits poorly with the fossil record, which shows massive evolutionary radiation in the group between 340 and 300 million years ago.

#9. Coelacanth

Coelacanths are elusive, deep-sea creatures, living in depths up to 2,300 feet below the surface. They can be huge, reaching 6.5 feet or more and weighing 198 pounds. Scientists estimate they can live up to 60 years or more. Extant coelacanths are unique because of the presence of a “fatty lung” or a fat-filled single-lobed vestigial lung, homologous to other fishes’ swim bladder. The parallel development of a fatty organ for buoyancy control suggests a unique specialization for deep-water habitats.

The primitive-looking coelacanth (pronounced SEEL-uh-kanth) was thought to have gone extinct with the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. But its discovery in 1938 by a South African museum curator on a local fishing trawler fascinated the world and ignited a debate about how this bizarre lobe-finned fish fits into the evolution of land animals. Coelacanths might best be described as occupying a side branch in the basal portion of the vertebrate lineage, closely related to, but distinct from the ancestor of tetrapods (four-legged vertebrates). They are supposed to be 400 million years old.

#8. Horseshoe Crab

Horseshoe crabs are marine and brackish water arthropods. They have a hard exoskeleton, 10 legs, and nine eyes scattered throughout the body. The two largest eyes are compound and useful for finding mates. The other eyes and light receptors are useful for determining movement and changes in moonlight. The telson (its long and pointed tail) although it looks intimidating, it is not dangerous, poisonous, or used to sting. Horseshoe crabs use the telson to flip themselves over if they happen to be pushed on their backs.

During full moons, new moons, and high tides in May and June, hundreds of thousands of horseshoe crabs converge on the Delaware Bay to breed. Horseshoe crabs have been around for more than 450 million years, making them even older than dinosaurs. They look like prehistoric crabs but are actually more closely related to scorpions and spiders.

#7. Brachiopod

Modern brachiopods occupy a variety of sea-bed habitats ranging from the tropics to the cold waters of the Arctic and, especially, the Antarctic. Most live in the relatively stable environments below the low-water mark in seawater of normal salinity, but some have wide salinity tolerances and live in more marginal marine environments, though few can survive the turbulence of the intertidal zone.

Brachiopods have a very long history of life on Earth (at least 500 million years). They first appear as fossils in rocks of earliest Cambrian age, and their descendants survive, albeit relatively rarely, in today’s oceans and seas. They were particularly abundant during Palaeozoic times (248 to 545 million years ago), and are often the most common fossils in rocks of that age.

#6. Nautilus

The chambered nautilus, Nautilus pompilius, also called the pearly nautilus, is the best-known species of nautilus. Unlike most cephalopods, the chambered nautilus lacks a larval stage. Their shells develop inside their eggs, and actually breach the top of the egg long before the nautilus actually hatches. They emerge as miniature versions of adults, roughly one inch in length.

The word “nautílos” literally means “sailor”. The shell of the Chambered Nautilus fulfills the function of buoyancy, which allows the Nautilus to dive or ascend at will, by controlling the density and volume of the liquid within its shell chambers. The oldest fossils of the species are known from Early Pleistocene sediments deposited off the coast of Luzon in the Philippines (500 million years ago). Although once thought to be a living fossil, the chambered nautilus is now considered taxonomically very different from ancient ammonites.

#5. Sea Sponge

They are organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate through them in order to obtain food and oxygen and to remove wastes, consisting of jelly-like mesohyl sandwiched between two thin layers of cells. They are the world’s simplest multicellular animals. If you tear up a sea sponge into thousands of microscopic pieces, those pieces will clump together and regenerate, turning into loads of new sea sponges. Sponges do not have nervous, digestive or circulatory systems.

Since about 90% of modern sponges are demosponges; fossilized remains of this type are less common than those of other types because their skeletons are composed of relatively soft spongin that does not fossilize properly. However, well-preserved fossil sponges from about 500 million years ago in the Ediacaran period have been found in the Doushantuo Formation.

#4. Velvet Worm

Velvet worms are ambush predators, hunting other small invertebrates by night. To subdue their prey (generally, invertebrates such as crickets, spiders, and woodlice) they squirt a sticky, quick-hardening slime from a pair of glands on their heads. After the prey is ensnared, the velvet worm bites into it, injecting digestive saliva that helps liquefy the insides for easier snacking. Depending on the species, a velvet worm can have between 13 and 43 pairs of feet.

They belong to a clade that has been around for over 500 million years. Fossilized marine versions of velvet worms from the Cambrian period have been found in the Burgess Shale in Canada (505 million years old) and the Chengjiang formation in China (520 million years old). Velvet worms are now considered to be close relatives of arthropods and tardigrades.

#3. Jellyfish

Jellyfish have no brain, heart, bones or eyes. They are made up of a smooth, bag-like body with umbrella-shaped bells and tentacles armed with tiny, stinging cells. The bell can pulsate to provide propulsion and highly efficient locomotion by squirting a jet of water from its mouth. These incredible invertebrates use their stinging tentacles to stun or paralyze prey before gobbling it up. The jellyfish’s mouth is found in the center of its body. From this small opening, it both eats and discards waste.

Since jellyfish have no bones or other hard parts, fossils are rare. Therefore, scientists have to look for so-called “soft fossils”, that is when organisms are quickly buried in sediment, they leave an imprint in the rock. Cubozoans and hydrozoans appeared in the Cambrian of the Marjum Formation in Utah, USA, -an area that used to be underwater, covered by the ocean- and they are supposed to be over 500 mya.

#2. Ctenophora

Ctenophores, variously known as ‘comb jellies’, ‘sea gooseberries’, ‘sea walnuts’, or ‘Venus’s girdles’, are voracious invertebrate predators that live in marine waters worldwide. A comb jelly is not a jellyfish though both have a similar gelatinous appearance. Interestingly, they are not even closely-linked relatives. Unlike jellyfish, comb jellies lack stinging cells, but ctenophores possess sticky cells called colloblasts (axial granular filaments) which on contact produce its granules to rupture and release an adhesive substance onto the prey.

Until fairly recently, no fossil ctenophores were known since their bodies are made up mostly of water, and the chances of leaving a recognizable fossil are very slim. Two species of fossil ctenophore have now been found that date back to the Late Devonian and to the mid-Cambrian period. According to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, comb jelly is at least 500 million years old.

#1. Cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria are a taxon of bacteria which conduct photosynthesis. They are not algae, though they were once called ‘blue-green algae’. They were the first known organisms to photosynthesize and produce free oxygen. By producing and releasing oxygen (as a byproduct of photosynthesis), cyanobacteria are thought to have converted the early oxygen-poor, reducing atmosphere into an oxidizing one, causing the Great Oxygenation Event and the “rusting of the Earth”, which dramatically changed the composition of the Earth’s life forms and led to the near-extinction of anaerobic organisms. In this way, cyanobacteria may have killed off much of the other bacteria of the time.

Stromatolites are layered biochemical accretionary structures formed in shallow water by the trapping, binding, and cementation of sedimentary grains by biofilms (microbial mats) of microorganisms, especially cyanobacteria. Stromatolites left behind by cyanobacteria provide ancient records of life on Earth by fossil remains which might date from more than 3.5 Ga ago (3.5 billion years).